the Voice of

The Communist League of Revolutionary Workers–Internationalist

“The emancipation of the working class will only be achieved by the working class itself.”

— Karl Marx

the Voice of

The Communist League of Revolutionary Workers–Internationalist

“The emancipation of the working class will only be achieved by the working class itself.”

— Karl Marx

Jan 4, 2021

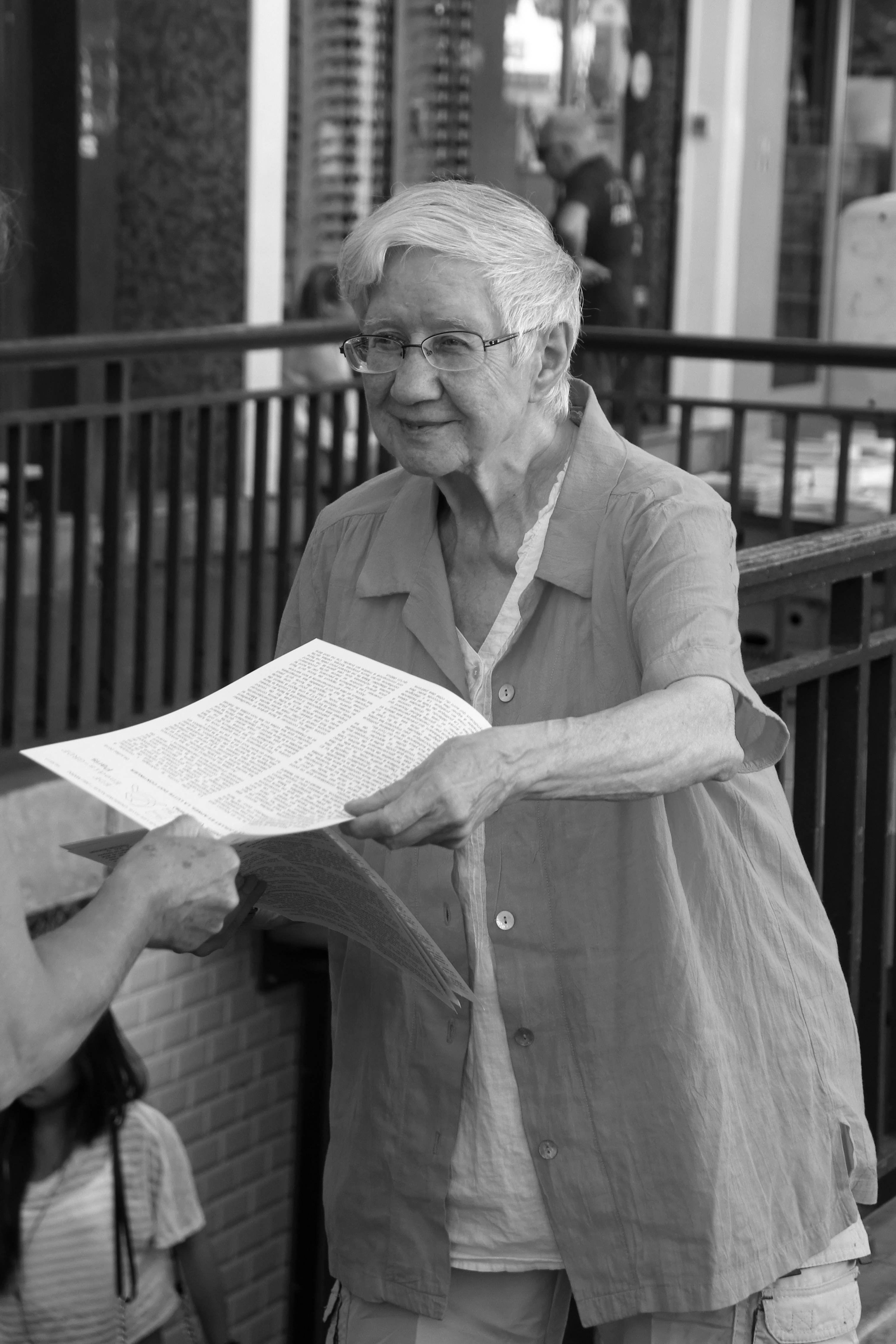

Rose Alpert Jersawitz was born August 3, 1935, in New York City. She died December 3, 2020, in Paris, France. Many of us knew her as Dorothy, a nickname given her many years ago.

Rose was the child of Jewish immigrants who came to this country like so many others in the early years of the 20th century, trying to escape the poverty and anti-Jewish pogroms that swept across areas of Eastern Europe ruled by the Russian czars. They arrived in a country where poverty, anti-Semitism and nativist attacks relegated them to impoverished ghettoes on this side of the Atlantic.

Rose was the youngest of five children. Her first years were spent in East Harlem. The kids she played with lived in families migrated from somewhere else. They came from Puerto Rico, from Southern rural Black areas, from southern Italy, from Ireland—and Rose’s Yiddish-speaking family from East Europe. “No one spoke the same English as our teachers in school spoke,” she said in her memoirs, “but we all understood each other.”

Her father had worked first in a tannery near Boston, from which he was driven out after trying to organize a union. In New York, he worked as an itinerant plumber. Her mother worked in a garment factory, until she was no longer able to keep up with the speed of the sewing machines. Then she took in washing. It was the ordinary life in that immigrant quarter, where no one made enough money to survive. In Rose’s own words from her memoirs, “all the kids stole,” and the ones who survived learned they had to fight to defend themselves.

Rose’s father died when she was six or seven. Her mother took the three kids still left at home, and moved to Toledo, Ohio, where she again took in washing. Eventually she remarried. Toledo was the place where Rose discovered strikes and picket lines. Her stepfather worked at the Jeep factory; her sister-in-law, at one of the glass factories.

In high school, she tried to organize a picket line to support a favorite teacher, who had been fired in the 1950s anti-communist crusade. Together with three other girls, she refused to be tracked, with boys into “shop” and girls into “home economics.” She was having none of it, and got herself into “wood shop.” She was expelled from school after punching a girl who threw an anti-Semitic slur at a friend of hers. And she discovered what deep roots racism had when her family was kicked out of their apartment after she brought home some friends, including a black student and another Jewish student—who looked “more Jewish” than Rose did, with her blond hair. As young men from her high school—boys, really—were being drafted, she started to pay attention to what was happening in the world. The U.S. war on Korea outraged her. “This big country making war on a little country,” she called it. And she read. Her brother, working at a newspaper in Toledo, was opening up the world to her with books.

Rose finished high school early, when she was only 15, then took the leap to go back to New York by herself. Winning a scholarship at NYU, she discovered college did not deliver on the hopes she had in education, and she slid into a kind of bohemian milieu in the West Village. It was there she met Jack Jersawitz, who challenged her on many of her ideas, and first of all on the fact that she followed the rituals of religion, even when she no longer believed. He was the first person she knew who called himself a “socialist” in the midst of McCarthy-period conformism. He conveyed to her his hopes for a communist future. And he got her in the habit of going to the public library.

It was at that point she was “kidnapped,” by two U.S. marshals, who took her to California, where her mother now lived. Effectively, she was arrested for being on her own while not being an adult. She was 16.

For six months she lived with her mother and sister’s family in one of the new “developments” springing up out in the desert near Los Angeles. Her health may have improved since she was eating regularly, but she felt like a prisoner. She executed a “prison break” from her family in the way that some young women still do—by getting married!

The marriage as such didn’t last a long time, but her association with Jack is what first opened her up to grappling with political ideas, and it was through him that she met comrades of the Socialist Workers Party, the Trotskyist organization led by James P. Cannon. She joined the SWP in 1953, when she was 18.

On June 19th of the same year that Rose decided to be a communist militant, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, members of the Communist Party, were put to death in the electric chair, convicted in a show trial of spying for the Russians. Hundreds of other communists and socialists were going to prison, including some in the SWP. The SWP, along with several hundred other organizations, was declared to be “subversive,” making membership grounds for expulsion from unions, government jobs—even working as street sweepers—teaching jobs, military commissions and even military pensions. Many unions or locals were dissolved. Tens of thousands of people lost jobs or places to live—unionists, strikers, communists, socialists, anarchists, organizers of rent strikes—anyone whose devotion to organizing working people made them suspect in the middle of the McCarthy period. The most interesting writers and actors were driven from Hollywood. Schools and universities purged their faculties. People who lost their enthusiasm were deserting organizations.

This was the situation in which Rose Jersawitz became a communist militant—the first person to join the SWP in California in four years. In the “Foreword” to her memoirs, entitled A Communist on Both Sides of the Atlantic, Rose explained that she could go against the reactionary winds of the time period because she knew nothing of what was going on in the country. Maybe. But her early life grounded her, giving her allegiance to her class, and so did her commitment to the socialist tradition she found. But she also had something that is essential in the makeup of a militant. She was not afraid to take an “unpopular” position, or to be practically alone, if that was necessary. In so doing, Rose brought others along with her.

In the darkest days of the witch hunt, she sold her newspapers, lost jobs, went to picket lines, found other jobs, stood up on crates to make a speech, was kicked out of apartments, went to protests against the police, found people to be in a class series about Marxism, found someone who put her up for awhile, convinced other people to join the SWP. In all of this her devotion was to the future she knew was embodied in the working class.

Her life ever since was lived in the same way. The SWP sent her to New York to help assimilate a group of youth who had quit another organization to join the SWP. Then she was sent to Chicago to help the group with a similar organizational problem. Eventually, she went back to California, where she ran as a candidate for city council in Berkeley in 1963.

By then she had become disturbed by the actions of the SWP giving priority to the various middle class movements that were beginning to pop up, a tendency that found its parallel on the political level, as the SWP began to consider the Cuban revolution a new road to socialism—built without the participation of the working class—seeing Castro as some kind of “unconscious” Marxist! She left the SWP and joined the Spartacist League, whose militants she thought had left the SWP based on the same criticism. Instead, she discovered that the SL not only seemed to be unable to approach the working class; it also seemed unwilling to her even to recognize the necessity of doing that.

In 1966, she went with other members of the SL to an international conference in London. There she met comrades of Voix Ouvrière, the predecessor to Lutte Ouvrière, the French Trotskyist organization. With the agreement of the SL, she was to stay in France for a month or two. Instead, she stayed for almost two years, working on an everyday basis with VO, going to public meetings, going to classes, taking part in meetings, passing out newsletters and selling VO’s paper at the plant gates and in the markets—and regularly sending reports back to the SL, the U.S. organization she was still part of.

In the 1960s U.S. that Rose came from, the left, “old” and “new,” had either equated the working class with the unions—or written it off. Rose discovered, working with VO, that it was possible to carry out political activity in the ranks of the working class, her class.

When she came back to the U.S. in early 1968, she didn’t come with the aim of starting a faction fight. She wasn’t carrying a franchise from Voix Ouvrière. But based on the work and discussions she had with them, she hoped to engage others in political work toward the working class. Quietly, without a lot of fuss. Nonetheless, she and others she interested in starting such work were soon shown the door.

She hadn’t started down this long path with the perspective of declaring a new organization. But it was necessary to begin work, based on what she knew.

She and several others moved to Detroit, where they all were hired into auto plants or in the phone company’s main operator office. Rose was hired into Chrysler’s Cut and Sew plant. Eventually, four, then five, then six newsletters were started in these workplaces.

While working in one factory, trying to establish a small network inside as the basis of each newsletter, each militant was at the same time distributing a newsletter at the gate of one of the other workplaces. And, of course, each of them also did the technical work to produce one of those newsletters—on manual typewriters and old-style mimeograph machines. Luckily, they all were graced with energy.

In 1971, after three years of work, Rose and the others decided it was necessary to define themselves politically—effectively, they had become an organization. They took a name for themselves, the Spark. They declared that their intention was to carry out political activity in the working class; that they based themselves programmatically on the Communist Manifesto, on the first four Congresses of the Third International and on the Transitional Program of the Fourth International.

In 1974, Rose moved to Baltimore, where she worked with comrades who were newer to the Trotskyist tradition. In 1985, she spent some months in San Francisco, as the result of an agreement between the Spark and Socialist Action to exchange militants.

Rose was beset most of her life with illnesses, one after the other. As the years went along, this made activity more difficult. At the same time, her long-time job in print shops was being wiped out as new technology took over.

Comrades of Lutte Ouvrière, with which Rose and the rest of the Spark organization have always maintained close ties, suggested that she might be able to find a niche in Paris, allowing her to go on contributing as a militant.

Up until that time, Rose had never settled long in one place—the longest was her 11 years in Baltimore. She was used to having her life turned upside down. But she was no longer a spring chicken. At 51, she would be moving to another country, speaking another language.

That meant learning late in life really to speak French, getting used to customs and cultural assumptions different than ones deeply imbedded in her own being. She took time to decide, but when she finally decided, she did it. For the rest of her life, the next 34 years, she functioned as a militant in France.

Rose still returned every year to the States, when Spark had its annual conference. She came back to help in 1988, when militants of Spark were involved in an election campaign together with a number of union activists. She sat in an old office in a nearly deserted building, contacting the media, arranging interviews and articles. She did the same thing in 2014, when Spark ran a directly communist election campaign with five of its militants.

Each spring, she was at the Spark booth in Lutte Ouvrière’s annual fete, talking to all those who came around, hoping to interest one of the young Americans, talking to them about the necessity of being a communist in the U.S.

Spark remained the organization she helped found, but French political life became her life. Whether in English or in French, she always acted on this necessity, which she expressed at the end of her memoirs: “I’ve always found it very important to tell people about socialism, about communism, about the possibility of changing things. That was almost a given, that was the basis of my life.... I had to talk to people, that meant I was doing something positive and that was important to me.”

Rose is the human link that ties all the rest of us to the Trotskyist tradition, the tradition that stretched back nearly 100 years, and which itself stretched back through Lenin to Marx.